The NY Fed just threw a real wrench into plans of those looking to sue banks and “put back” mortgages due to “bank’s misrepresentations” on mortgage documents. The line of thinking to this point was that is was the banks who simply misrepresented the loans they were put into securities and selling to investors. This study counters that, rather it says, it was “investors” a group previously thought to be marginal buyers of homes during the bubble, who were the primary driver of the rapid run up in prices and subsequent decline. Further it shows how they accomplished this, through fraudulently misrepresenting themselves as “owner occupants” on applications.

Now the conversation has to change. If these fraudulent investors were the primary cause of the bubble and its aftermath, and they accomplished this through fraud, then the banks “put back” risk just got a whole lot smaller.

The banks who sold securitized loans are responsible for the “put back” risk if they knowingly misrepresented the loans that were placed into the security. In fact, that is a major piece in Bank of New York v Bank of America lawsuit (as well as others). One of the main prongs of that suit is that Bank of America misrepresented the % of owner occupied homes in the securities they were selling. This study shows that in fact it was the applicants who were making the misrepresentation.

Fitch describes the put back process:

In RMBS transactions, reps and warranties are given by the originator, issuer or other appropriate party, covering several areas, including the legality of the mortgage loan, the lien status, and condition of the property. In addition, some of the reps and warranties address compliance with the originator’s underwriting standards and a smaller number of transactions have specific reps and warranties for fraud. However, there are several challenges to relying on reps and warranties to remove loans from RMBS deals for a breach due to underwriting or misrepresentation/fraud.

For many subprime loans, the program guidelines allowed the originator to base qualification on features such as stated income. Assuming that the originator’s underwriting standards did not require the verification through another means, or that a “reasonableness test” be conducted, the failure to perform these steps would not be an exception to their underwriting standards. Therefore, if the borrower or broker misrepresented the actual income, it is fraud on their part, but is it a breach of the reps and warranties? The same question would apply to borrowers who have artificially enhanced their FICO.

Most pooling and servicing agreements that Fitch reviewed indicate that any party to the transaction (typically, the issuer, servicer, master servicer, or trustee) who becomes aware of a suspected breach to the reps and warranties should provide notice to the trustee (or in some all other parties). However, unless there is a reason that research is conducted to specifically look for a breach, finding potential breach situations typically requires an awareness and identification by the servicer while conducting their functions. Directions as to the process after notification are somewhat varied, but in general, if a breach is determined, the trustee will facilitate the request for repurchase of the loan from the transaction. Fitch believes that risk management firms that track potential repurchase candidates and monitor the repurchase process can enhance the effectiveness of representations and warranties. However, in today’s environment, one of the situations which could occur would be that the original provider of the reps and warranties is no longer in existence or has filed bankruptcy.

This is why these suits are settling for pennies on the dollar. While to be sure in many cases there was bank fraud, it is becoming more apparent that on a larger percentage it was applicant fraud and the banks are not responsible for that. The process of going over hundreds of thousands or loans to determine what happened and then to litigate it would do only one thing, make the lawyers rich. People can argue about the number of pennies on the dollar they should be responsible for but as more of these studies come out, I just have to think the banks will begin to dig their heals in more and those filing suits will want whatever they can get (meaning lower settlements)

What is really surprising to me is that up until now the common thought process was that the home buying activity among “investors” was on the fringe and not as widespread as it was. In fact, the NY Fed now says that this is the main reason policies like HAMP have been so ineffective:

Our findings regarding the role of investors in the housing boom and bust and the high rate at which they defaulted after 2007 also has important implications for the design of effective, equitable and targeted assistance programs. While the majority of home-owner assistance programs developed over the past several years have been targeted to owner-occupants, many have experienced relatively low take-up rates. If, as indicated here, a large share of defaulters are not living in the collateral home, then programs such as HAMP may not be effective in stemming foreclosures.

I am reminded of a story Wilbur Ross told in I think 2009 (I am paraphrasing it as I do not have the exact story in front of me):

Ross and his son were playing golf at their club in Florida in 2007 (or ’08). Their caddy, knowing who he was said “Mr. Ross, can I ask you a financial question?”. Ross was slightly annoyed (he just wanted to gold with his son) but said ok. The caddy said “I own several condos in Las Vegas and they are underwater, do you think housing will come back soon and I should hold them or should I just take my losses now”. Ross thought about it and said. “Well, can you rent them? What is the area around them like? Is it still growing? Are they in a desirable neighborhood? How close to the strip are they?”. The caddy looked at him and said “I’m not sure”. Ross asked “Why?”. The caddy said “I’ve never been to Las Vegas”

I have always thought that story was more indicative of what happened pre-crash but it would seem based on the studies referenced, it wasn’t (full pdf of report at the end). Now that we are getting better data sets from the era, it seems to be being proven it was, especially in the bubble states.

The data now shows the caddy (maybe not this guy but we’ll use him as an example) and many, many more investors were indicating they were going to move into the properties they were buying and applying for “owner occupied” loans. By doing this they were granted lower downpayment requirements and lower interest rates. This allowed them to leverage what money they did have and buy more properties (5% or lower downpayment required vs 20%). It also meant that when the music stopped, they easily walked away from the properties. We all knew this took place, but the paper here show it was FAR more widespread than previously thought.

I have snipped a few parts I feel important and some conclusions the authors drew (note: these are snipped from various sections and it is not a continuous part of the paper) . Please read the full report yourself (only 52 pages)

Abstract:

We explore a mostly undocumented but important dimension of the housing market crisis: the role played by real estate investors. Using unique credit-report data, we document large increases in the share of purchases, and subsequently delinquencies, by real estate investors. In states that experienced the largest housing booms and busts, at the peak of the market almost half of purchase mortgage originations were associated with investors. In part by apparently misreporting their intentions to occupy the property, investors took on more leverage, contributing to higher rates of default. Our findings have important implications for policies designed to address the consequences and recurrence of housing

market bubbles

Haughwout et al (2008), for example, indicate their suspicion that miscoding of occupancy status in loan-level data may help to explain the large increase in early nonprime defaults that are unexplained by observable – i.e., reported – characteristics of loans and borrowers.Fitch (2007) found evidence of occupancy misrepresentation in two-thirds of the small sample of subprime defaults they examined. It is thus desirable to identify a mortgage data source that allows the analysis of borrowers without relying on the information that is self-reported by the borrower on the mortgage application.

Our data allow us to “see through” the self-reported information captured on the mortgage application, and show precisely this – an increasingly large discrepancy between mortgage application occupancy self-reports and the number of first-liens on the credit report during the crucial 2004-2006 period. These results thus leave open the question of the role of these investors in the subsequent increase in defaults and delinquencies

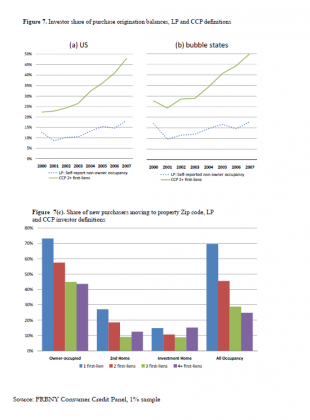

Figure 7 contains three panels which explore the relationship between occupancy selfreporting on mortgage applications and borrowers’ first-lien counts for our matched CCP-LP sample. In panel (a), we plot the proportion of new nonprime purchase originations by self-reported occupancy status (from LP) and number of first-liens (from CCP). The dashed line plots the proportion of balances taken out by borrowers who checked either “2nd home” or “investor property” on the mortgage application, while the solid line shows the proportion of balances originated by these same borrowers who, after closing this mortgage, simultaneously have two or

more first-liens.Comparing the two series provides some insight into the value of self-reported occupancy status. First, at the beginning of the period the two series are reasonably close together, but even in 2000 there is a significant discrepancy between what borrowers report on the mortgage application and the number of properties they own. Over time, the proportion of new originations by borrowers who acknowledge that they will not use the home as their primary residence (the dashed line) increases slowly, and is fairly flat at 13-15% for the crucial 2004-2006 vintages. While we are including second homes, balance weighting and using only purchase mortgages, this pattern is similar to the results found by Mayer, Pence and Sherlund (2008). Meanwhile, however, the proportion of borrowers who have 2 or more first-lien mortgages rises much more quickly, and approaches 41% by 2006. The bubble states, shown in Figure 7(b), exhibit the same pattern, although in somewhat more extreme, where in 2006 the gap between self-reported occupancy status and the number of first-liens reached 30 percentage points. In other words, many of the borrowers who claimed on the mortgage application that they planned to live in the property they were purchasing had multiple first-lien mortgages when the transaction was complete. Mayer, Pence and Sherlund (2008) accurately report that borrowers’ self-reported occupancy status was not changing dramatically during this period, but they are unable to observe the change in the characteristics of borrowers who report themselves as owner-occupants. In fact, the importance of investors as defined in the CCP – borrowers who have 2 or more first-liens on their credit reports – expanded sharply during this period, especially in the bubble states

While it is possible that all of these borrowers intended to live in the purchased property, it seems unlikely. In addition, the matched data allow us to track whether the individual changed addresses after closing the mortgage, and whether they moved to the same zip code recorded for the property. Figure 7(c) shows, by borrowers’ self-reported occupancy status and the number of first liens on their credit reports, the percentage who changed addresses to the zip code containing the property within two years of originating a nonprime purchase mortgage. Unconditional on self reported occupancy status we find respectively 70% and 25% of single and four first-lien holders to have moved to the property zip code within two years of the new purchase. The data indicate further that 73% of those who claim owner occupancy while holding a single mortgage changed addresses and their new zip code matches that of the property. By contrast, only 43% of those who claimed owner occupancy on the mortgage application while carrying four or more first-liens prior to closing moved to the property zip code within two years. Unsurprisingly, relatively low shares (under 30%) of those who reported the property as a second home or investor property moved to the property zip code within two years. While the evidence cannot be definitive, we take this as suggestive of significant occupancy misrepresentation in nonprime mortgages during the boom.

We conclude that, given down payment requirements in the prime market, investors were able to increase their leverage by disproportionately using nonprime securitized mortgages, and were a major driver of growth in that important market segment. By declaring an intention to live in the properties collateralizing these loans, investors were able to reduce both the interest rates and the minimum downpayments, with the latter being the most valuable for our buy and flip investors.

We conclude from our analysis that mortgage borrowing by investors – defined as those with multiple properties in their portfolios – increased substantially during the boom, especially in those markets where house price increases were particularly pronounced. We find evidence of increases in both the extensive margin – new investors entering the marketplace – and the intensive margin – increased exposure to residential real estate among previous investors.

These results contrast with previous discussions of the role of investors in the mortgage marketplace, and underscore the benefits of the FRBNY CCP for analyzing these questions. Mayer, Pence and Sherlund (2008), for example, conclude “because our data show that [self-identified] investors were a small or declining share of overall originations [of non-prime mortgages], it seems unlikely that they accounted for much of the rise in the overall delinquency rate unless they increasingly misrepresented themselves as owner-occupiers or their unobserved characteristics deteriorated over time.” (2009, pg. 44, emphasis added). Our data allow us to “see through” the self-reported information captured on the mortgage application, and show precisely this – an increasingly large discrepancy between mortgage application occupancy self-reports and the number of first-liens on the credit report during the crucial 2004-2006 period. These results thus leave open the question of the role of these investors in the subsequent increase in defaults and delinquencies.

Full Report:

NY Fed Housing Study (click to open pdf)